No Impunity - Bring the killers of journalists to justice

November 2 is International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists. Nine Australian journalists have been murdered with impunity.

Their killers have literally been getting away with murder. All but one of the cases involved a journalist working in a conflict zone overseas.

The sole domestic case, of Juanita Nielsen, remains unsolved despite considerable attempts by police forces to find her body and to bring homicide charges against her murderers.

The remaining eight cases, the bulk of which date back to the Indonesian invasion of East Timor in 1975, are a sorry tale of ongoing government indifference, and a lack of will to investigate the murder of Australian journalists. Read the stories of the nine murdered Australian journalists below.

Threats and attacks of various forms continue against journalists and the media community worldwide, and impunity continues to be the norm in the majority of cases. MEAA is part of the global campaign to end impunity over the killing of journalists - see the video. UNESCO’s World Trends in Free Expression and Media Development report, contains the 2017 data on journalist killings and the status of judicial investigations.

Juanita Nielsen

Sydney journalist and editor Juanita Nielsen disappeared on July 4, 1975. Nielsen was the owner and publisher of NOW magazine. She had strongly campaigned against the development of Victoria Street in Potts Point, in the electorate of Wentworth, where she lived and worked.

On September 30, 2015, MEAA wrote to Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull as part of an International Federation of Journalists global campaign urging UN member states to sign and ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearances. Enforced disappearances, abductions and the vanishing of media workers is a reality in too many countries in the Asia‐Pacific region – and Australia is not immune as demonstrated in the case of Nielsen. MEAA urged the Prime Minister to consider signing and ratifying the convention as a way of sending a strong signal that Australia and will “prevent enforced disappearances and combat impunity for the crime of enforced disappearance”.

MEAA’s letter was referred to Attorney-General George Brandis whose chief of staff responded on February 9, 2016: “The Australian Government considers that Australia’s laws and policies are generally consistent with obligations in the convention and that existing criminal offences in relation to elements of enforced disappearance (such as abduction or torture) are adequate. Additionally, Australia already has international human rights obligations prohibiting conduct covering enforced disappearance. Accordingly, Australia is not intending to become a party to the convention at this time.”

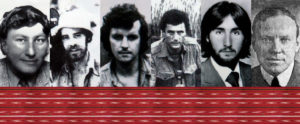

The Balibo Five and Roger East

The Balibo Five, from left to right - Gary Cunningham, died aged 27; Brian Peters, died aged 24; Malcolm Rennie, died aged 29; Greg Shackleton, died aged 29; Tony Stewart, died aged 21. Far right, Roger East, died aged 53.

Brian Peters, Malcolm Rennie, Tony Stewart, Gary Cunningham and Greg Shackleton were murdered by Indonesian forces in Balibo, East Timor, on October 16, 1975. On November 16, 2007, NSW Deputy Coroner Dorelle Pinch brought down a finding in her inquest into the death of Peters. Pinch found that Peters, in company with the other slain journalists, had “died at Balibo in Timor Leste on 16 October, 1975 from wounds sustained when he was shot and/or stabbed deliberately, and not in the heat of battle, by members of the Indonesian Special Forces, including Christoforus da Silva and Captain Yunus Yosfiah on the orders of Captain Yosfiah, to prevent him from revealing that Indonesian Special Forces had participated in the attack on Balibo. “There is strong circumstantial evidence that those orders emanated from the Head of the Indonesian Special Forces, Major-General Benny Murdani to Colonel Dading Kalbuadi, Special Forces Group Commander in Timor, and then to Captain Yosfiah.”

In the more than 40 years since this incident Yunus Yosfiah has not lived in obscurity. He rose to be a major general in the Indonesian army and is reportedly its most decorated solider. He was commander of the Armed Forces Command and Staff College (with the rank of Major General) and Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces Social and Political (with the rank of Lieutenant General). He was chairman of the Armed Forces Faction in the Indonesian National Assembly. He retired from the army in 1999.

He is also a former minister of information in the Indonesian government of President Bacharuddin Jusuf Habibie. In February 2007 Yosfiah unsuccessfully contested the election for party chairmanship of the United Development Party (PPP). In 2017 Yosfiah has been frequently mentioned in press reports regarding his involvement as chairman of mobile top-up company Mi1 Global Indonesia, a business being reviewed by the Indonesian Financial Services Authority.

And yet despite his prominence in public life in Indonesia, the Australian Federal Police has not pursued the 2007 coronial finding which named him as allegedly having ordered the death of Brian Peters and his four colleagues. Indeed, the AFP appears to have done little to conduct any investigation in Indonesia or with Indonesia authorities.

Almost two years after the coronial finding, on September 9, 2009, the AFP announced that it would conduct a war crimes investigation into the deaths of the five journalists. However, on October 21, 2014 the AFP announced it was abandoning its five-year investigation due to “insufficient evidence to prove an offence”. MEAA said at the time: “Last week, the AFP admitted that over the course of its five-year investigation it had neither sought any co-operation from Indonesia nor had it interacted with the Indonesian National Police. The NSW coroner named the alleged perpetrators involved in murdering the Balibo Five in 2007. Seven years later the AFP has achieved nothing. It makes a mockery of the coronial inquest for so little to have been done in all that time. This shameful failure means that the killers of the Balibo Five can sleep easy, comforted that they will never be pursued for their war crimes, never brought to justice and will never be punished for the murder of five civilians. Impunity has won out over justice.”

Roger East was a freelance journalist on assignment for Australian Associated Press when he was murdered by the Indonesian military on the Dili wharf on December 8, 1975. MEAA believes that in light of the evidence uncovered by the Balibo Five inquest, there are sufficient grounds for a similar probe into Roger East’s murder and that similarly, despite the passage of time, the individuals who ordered or took part in East’s murder may be found and finally brought to justice. However, given the unwillingness to pursue the killers of the Balibo Five, MEAA does not hold out great hope that Australian authorities will put in the effort to investigate East’s death. Again, it is a case of impunity where, literally, Roger’s killers are getting away with murder.

Paul Moran

Paul Moran, a freelance cameraman on assignment with the Australian Broadcasting Corporation to cover the Iraq war, was killed by a suicide bomber on March 22, 2003 leaving behind his wife Ivana and their then seven-week-old daughter Tara. Paul was the first media person killed in the 2003 Iraq war. The attack was carried out by the group Ansar al-Islam — a UN-listed terrorist arm of Al-Qaeda. According to US and UN investigations, the man most likely responsible for training and perhaps even directly ordering the terrorist attack is Oslo resident Najmuddin Faraj Ahmad, better known as Mullah Krekar.

Krekar had been imprisoned in Norway, guilty of four counts of intimidation under aggravating circumstances. He was released from prison on or around January 20, 2015. It was revealed that he would be sent into internal “exile” to the village of Kyrksaeteroera on the coast, south-west of Trondheim.

On February 10, 2015 MEAA wrote to Justice Minister Michael Keenan and AFP Commissioner Andrew Colvin once more, stating: “We are deeply concerned that if those responsible for killing Paul are not brought to justice then they are getting away with murder. You would be aware that the United Nations General Assembly has adopted Resolution A/RES/68/163 which urges member states to: ‘do their utmost to prevent violence against journalists and media workers, to ensure accountability through the conduct of impartial, speedy and effective investigations into all alleged violence against journalists and media workers falling within their jurisdiction and to bring the perpetrators of such crimes to justice and ensure that victims have access to appropriate remedies’.”

On April 15, 2015, the AFP’s Deputy Commissioner Operations Leanne Close replied, saying that there was insufficient information available to justify an investigation under section 115 of the Criminal Code Act 1995 (Harming Australians) and that despite the new information on Krekar’s movements, AFP would not be taking any further action.

On February 20, 2015, in the aftermath of the massacre in Paris of journalists, editorial and office staff at the Charlie Hebdo magazine, it was reported that Krekar had been arrested for saying in an interview that when a cartoonist “tramples on our dignity, our principles and our faith, he must die”. It is believed Krekar was subsequently arrested on a charge of “incitement”. Krekar was arrested in prison in Norway on November 11 "in a coordinated police swoop on Islamist militants planning attacks."

In mid-March 2016 Norwegian media said Krekar had been released from jail after a court found him not guilty of making threats. In mid-March 2017 a court in the Italian south-Tyrol town of Bolzano was adjourned until October 23, 2017 and it is expected that charges will be laid against Krekar who still resides in Norway and five other individuals involving telephone conversations. It has been alleged by the Italian prosecutor that some of the suspects in the case are seeking to overthrow the government of Iraqi Kurdistan and replace it with a theocratic state based on sharia law.

Tony Joyce

ABC foreign correspondent Tony Joyce arrived in Lusaka in November 21, 1979 to report on an escalating conflict between Zambia and Zimbabwe. While travelling by taxi with cameraman New Zealander Derek McKendry to film a bridge that had been destroyed during recent fighting, Zambian soldiers stopped their vehicle and arrested the two journalists. The pair were seated in a police car when a suspected political officer with the militia reached in through the car’s open door, raised a pistol and shot Joyce in the head. Joyce was evacuated to London, but never regained consciousness. He died on February 3, 1980. He was 33 and was survived by his wife Monica and son Daniel.[xi]

Zambia's President Kenneth Kaunda later alleged that Joyce and McKendry were fired at because they had been mistaken for white "Rhodesian commandos" who had crossed the border. McKendry was never asked by the Zambians to identify the gunman and he was even locked up for refusing to support a story that the shooting was a battlefield incident.

There exist serious allegations that the Australian Government never sought justice for his murder. Political reporter Peter Bowers is quoted from an ABC interview in 1981: “The Prime Minister (Malcolm Fraser) is a party to the cover-up to the extent he is no longer pressing the Australian position and demanding an inquiry [by the Zambians]. Not only that, but he went into parliament and made excuses for the Zambian authorities failing to find out what had really happened. Clearly Mr Fraser has seen it to be in the national interest to no longer press cover-up of a crime in Zambia, to turn a blind eye, to connive. Why? Because he is obviously concerned it could affect his personal relationship with Kaunda [as well as] his whole black-African strategy which is one of his strongest commitments in the international arena.”

MEAA hopes that, despite the passage of time, efforts can be made to properly investigate this incident with a view to determining if the perpetrators can be brought to justice.

Read the impunity chapter in MEAA's 2017 press freedom report here.