Remembering Phil Chubb

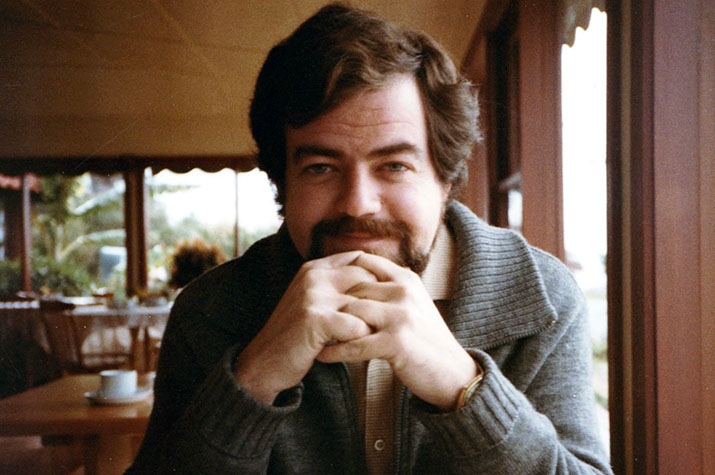

Phil Chubb during the 1980s (photo by the Chubb family).

Philip Chubb, a distinguished journalist, journalism academic and former Victorian branch president of the Australian Journalists’ Association (now MEAA Media), passed away on November 9 after a battle with cancer, aged 66. In this extract from a eulogy delivered in Melbourne on Wednesday, November 15, colleague Margaret Simons recalls Chubb’s union activism.

Phil was my first boss in journalism [at The Age newspaper]. I was “his” cadet for six weeks during the [1982 Victorian] election campaign that brought John Cain to power.

I got to watch Phil work – heard him do phone interviews, negotiate off the record conversations on to the record and work and develop his contacts.

I heard him talk about independence, of thought and of action. I read his astonishing run of front page stories. I was a very green and naïve girl from Adelaide. Phil showed me what journalism was, and how it was done.

Somewhere in there this gruff, gentle man and I became friends. It was a friendship that stuck for 35 years.

The thing I can talk about here that others know less about is his union activism. In the early 1980s Phil decided, rightly, that the Victorian Branch of the Australian Journalists Association (AJA) needed reform and modernisation. Phil was mostly a gentle man, but when he decided to move on someone, he was ruthless.

He ran a successful campaign and became president of the branch. I was union rep. at The Age, (“Mother of the Chapel” we used to call it, to reflect the old terminology the printers used of “father of the chapel”) and he persuaded me to join him on the branch committee.

So many of the things we now take for granted were won during that period of unionism, and might not have been won as quickly or as well without the reform Phil lead.

We oversaw, for example, the establishment of industry superannuation – the AJA was at the centre of that campaign, and before it was a legal requirement the 3 percent employer contribution was won in an industrial campaign at The Age in 1986.

Phil was the leader, the strategic brain. I was the one who got to lie in front of a truck on a picket line.

Which, of course, I gave him plenty of shit about.

He said that if people remembered him as having been decent, “not just one of those macho newsroom boyos”, then that would be good.

Just a week ago, again with him in his hospital bed, we were recalling the Cain Government’s workplace safety legislation that delivered great power into the hands of workplace safety reps at a time when our colleagues were being struck down with the plague of RSI. It is hard to convey, here and now, how frightening it was as our colleagues fell victim to this disabling complaint which accompanied the haphazard introduction of new technology. They were scared that they would never work again and faced with a management sceptical that their injuries were real.

Phil was writing about the laws as a journalist, and as unionists we were able to use them to press for action.

There was an ergonomist’s report that had been done on the newsroom for management, but the House Committee had been refused a copy. Phil and I realised that the new Work Safety laws meant that if I requested it as workplace safety officer, they were legally obliged to share it with me.

Of course it wasn’t that simple. We had to wait for them to get legal advice and recognise their obligations. Then I was called to the top floor one day without warning, and it was handed to me in a sealed envelope that I was not allowed to open right away. When I got back to my desk I found in the envelope a note saying that the report was being given to me on the condition that I not share it with any other person, and certainly not with the union. In other words, I couldn’t use it.

I took it to Phil. Was I to be in legal trouble if I ignored the directive? I still remember him looking at me and saying “Fuck ‘em, Meg. Leak it”. He promised me the full backing of the union if there were any consequences. And so it was done. And of course, management never acted against me, and thanks to the pressure we could exert, some improvements to working conditions were made.

Phil understood what the reform to work safety laws meant politically, and for our colleagues, and for those many workers for whom this was a matter of life and limb.

He brought that same combination of big picture and forensic detail to Labor in Power, his Gold Walkley Award winning documentary. I watched it again on YouTube recently. Many others since have catalogued those years. Phil was the first, and all the others have drawn on his work. The interviews and scripting are incredible. They changed the way that kind of journalism is done. Phil is never heard and never seen, but his intelligence and sensibility are certainly on display.

Unusually for the time, Phil as union branch president backed action on sexual harassment, in a couple of very nasty cases the details of which remain confidential. Suffice to say women were coming to their workplace in fear, and when management acted at all it was to suggest that the women – not the man who was harassing them – should be moved to new workplaces. Truly.

There are women here today who will remember that the union acted on their behalf – arguably not enough – but at a time when this was by no means to be taken for granted.

There were other male unionists who didn’t think it was an issue. Phil got it straight away as a simple matter of justice and human dignity – his core values.

Phil tried hard to be a cynic. It would be wrong to call him an idealist.

But his key aspiration was to be a decent human being. He had a low tolerance for people who declined to take moral responsibility for tackling injustice.

He told me this just a few days ago. He said that if people remembered him as having been decent, “not just one of those macho newsroom boyos”, then that would be good.

No worries there, old friend.

Margaret Simons, associate professor in the School of Media, Film and Journalism at Monash University.